Murder in Minneapolis, 1936

It’s map Monday.

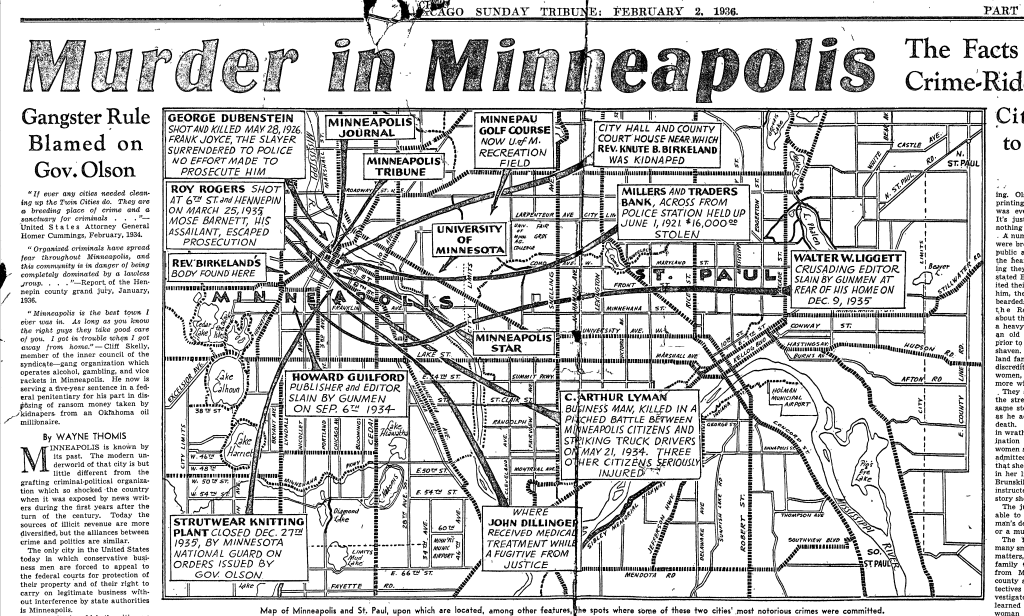

Published by the Chicago Tribune in 1936, this “Murder in Minneapolis” map was designed to illuminate “the Facts about a Crime-Ridden City.” Compiled as the city hit bottom, the diagram reflects the town’s unsavory reputation in 1936. Between the Teamsters’ strike of 1934 and 1946–when Minneapolis earned the ignominious title of “anti-Semitism” capital of the United States–the city was regarded with fascinated horror by the rest of the country. One report after another declared that Minneapolis was beyond repair–its economy in tatters, its social relations poisonous, and its criminal element unchallenged. In the article accompanying this diagram, Tribune reporter Wayne Thomis wondered: “Why is it that the decent-law-loving men and women who live in that city and state do not take some bold direct action to eliminate gangsters, gang lawyers and hoodlum-befriending politicians?”

This “expose” of Minneapolis was compiled by the conservative Chicago Tribune, which laid responsibility for the city’s lawlessness at the feet of the state’s political radicals. The accompanying article was a screed against Minnesota’s Governor Floyd B. Olson, who grew up on the Northside of Minneapolis and went on to become District Attorney of Hennepin County before winning the governorship. In the early years of the Great Depression, Olson became nationally known for his fiery radicalism, declaring in 1934: “I am not a liberal. I am what I want to be — a radical.” He was seen as presidential material in 1936, a challenge from the left to Franklin Delano Roosevelt. Conservatives (including Tribune publisher McCormick) hated him for his radical rhetoric, though he governed pragmatically until he died prematurely from stomach cancer, seven months after this article was published.

The map highlighted some of the deaths associated with the labor violence that had rocked the city since the global economic collapse. The article and accompanying graphic also detailed a series of murders that were blamed on local mobsters, including those of crusading journalists Walter Liggett and Howard Guilford, who sought to expose the connections between the state’s political and underworlds.