Ice Cream and Civil Rights: Fosters Sweet Shop on the 1920s Northside

Anthony B. Cassius remembers that the civil rights movement in Minnesota got started over ice cream in a modest North Minneapolis confectionary. In the early 1930s, a man named Herbert Howell, who worked for the African-American newspaper the Spokesman, “got us together and we formed what was known as the Minnesota Club. Clifford Rucker was a prominent man in it. Herbert Howell, Lena Smith, Dr. Brown and myself, there was about eight of us. We met once a month in Fosters Sweet Shop on Sixth and Lyndale. We met in the back and all they wanted us to do if we met there was to buy a dish of ice cream. So we’d meet from about 7:30 at night ’til about 9:00.”

The Minnesota Club protested the screening of “The Birth of the Nation,” the film lionizing the Ku Klux Klan that returned to the Twin Cities in late 1930. They must have discussed the situation of Arthur and Edith Lee, who bought a house at 4600 Columbus Avenue South only to find themselves confronted by a white mob in 1931. Minnesota Club member Lena Olive Smith came to their defense as an attorney and representative of the NAACP, supporting their desire to remain in the all-white neighborhood in the face of death threats. They surely debated the problem of housing and jobs, as African Americans could only find work on the railroads or in the Athletic Club, the Elks Club or the Curtis Hotel in the 1930s. “Seventy-five percent of all the people living in the city of Minneapolis were on relief,” Cassius remembered.

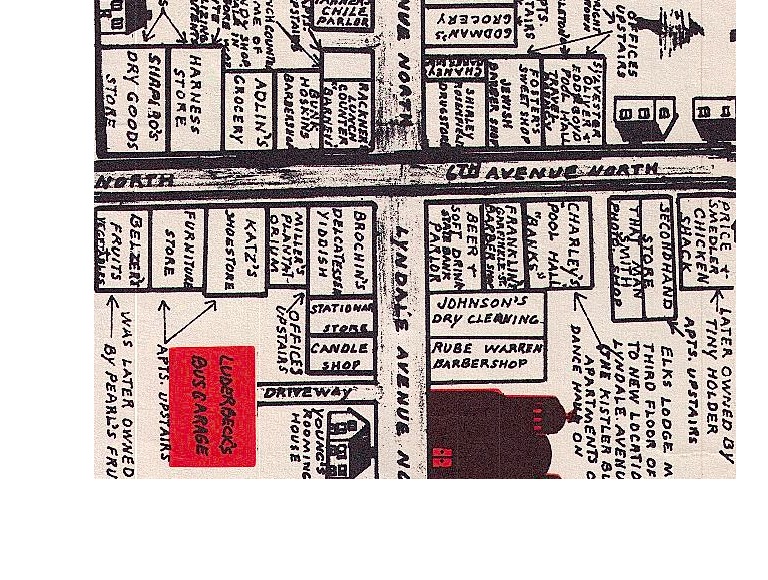

After reading a 1982 interview with the civil rights activist, I looked in vain for more information about Fosters Sweet Shop but was unable to locate even a complete address for the establishment that Cassius remembers as hospitable to these early organizing efforts. Then recently, I stumbled across a map drawn by Clarence William Miller, who had immortalized his memories of 1920s North Minneapolis in a detailed diagram that I have excerpted here. Miller wrote an accompanying “lament” that remembered Sixth and Lyndale as a “beautiful and busy intersection” that was the center of African American life in the 1920s. Since African Americans were unwelcome downtown, “the Avenue was their only outlet for enjoyment after six days of hard labor on their jobs in those years. It was said that a Sunday was not a Sunday if you didn’t get to 6th Avenue.”

Look for Foster’s Sweet Shop in the top right quadrant of this map, between the “Jewish Barber Shop” and “Sylvester Oliver and Edie Boyd Pool Hall.” This detail is taken from the larger map, which is in the collection of the Upper Midwest Jewish Historical Society collection at the University of Minnesota. My thanks to archivist Kate Dietrick for digitizing the map and sharing my enthusiasm about its importance for Minneapolis history.