“Is there no surety for those who inhabit the cities of the dead?”

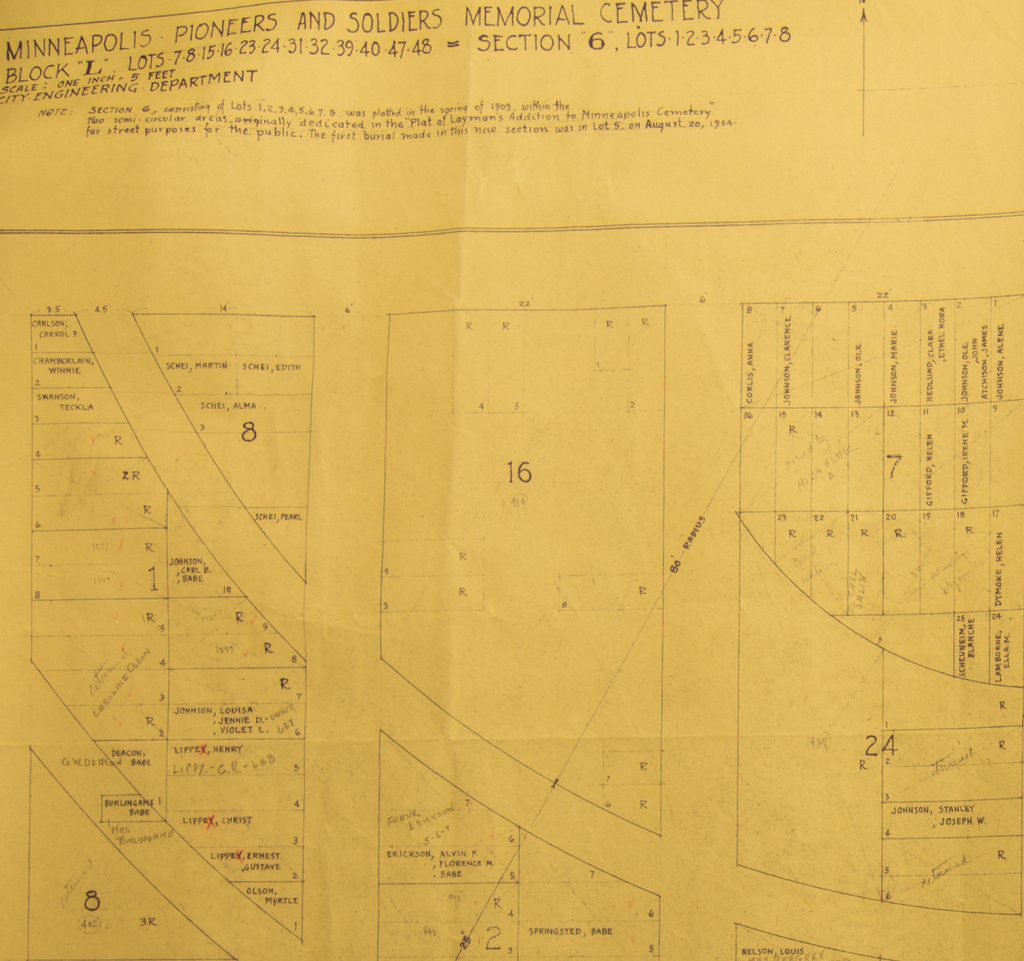

It’s map Monday. And today we have a map that shows the burial plots in Soldiers and Pioneers’ Cemetery, another item from the tower archives at City Hall. Over the last several weeks, our team has been working to illuminate the holdings of this forgotten repository.

This map is one of many of the records associated with this cemetery–the oldest burial ground in the city–in the tower archives. Located at the intersection of Lake Street and Cedar Avenue, it is the only cemetery in Minnesota to be listed as an individual landmark on the National Register of Historic Places. Open to people of all races and economic backgrounds during the 70 years it accepted new burials, this cemetery provides a wonderful glimpse into the early years of the growing city.

Before Minneapolis was imagined as a city, this land was the homeland of the Dakota, who had very different rituals for death than those observed by new American settlers. Instead of trying to bury bodies in the frozen earth, Indians elevated corpses onto platforms and surrounded them with food that could ease the journey to the spirit world. New settlers were fascinated by these Indian burial grounds; but part of claiming this land as their own was establishing a more familiar kind of venue for burying their dead. In 1853, Martin Layman–one of the earliest Americans to stake a claim on the west side of the Mississippi River, before the land was opened to settlement– offered some of his land for this purpose.

The first burial in what became known as Layman’s Cemetery took place in September of that year, when a ten month old baby was laid to rest. Carlton Keith Cressey was the son of W.E. Cressey, the founder of the First Baptist Church in Minneapolis. In the decades that followed, Carlton was joined by dozens of prominent Minnesotans and by World War I, the 28 acre site contained 20,000 graves, though only a small percentage of these had markers.

No provision had been made for the ongoing maintenance of the cemetery and after the death of Martin Layman the grounds began to decline. In 1917, local activists petitioned the city council to take action. City officials agreed that the historic burial ground had become a “moral hazard” and menace to public health, blocking burials and then closing the cemetery for good in 1919. The cemetery seemed destined to meet the bulldozers and preparations were made to sell the land to a private developer. Thousands of Minneapolitans removed the bodies of family members to Lakewood Cemetery or Crystal Lake Cemetery.

In the spring of 1925, a group of influential citizens mobilized against these plans, organizing the city’s first historic preservation movement. A group that included the Grand Army of the Republic, Sons of the Revolution, the Daughters of the American Revolution (D.A.R.), and the National Society of Colonial Dames formed the Minneapolis Cemetery Protective Association (M.C.P.A.), which recruited the Minneapolis Journal to this cause. “Is there no surety for those who inhabit the cities of the dead?,” the newspaper demanded on April 28, 1925. “Have they no guaranty that their last resting places shall not be violated?” They rallied to save Layman’s Cemetery as an important site of the early history of Minneapolis and lobbied the City of Minneapolis to take over the cemetery as a memorial to the pioneers and soldiers of Minneapolis.

In May 1927, the Minneapolis City Council voted to purchase Layman’s Cemetery. It rejected plans to make the cemetery into a public park. Instead it decided to implement improvements–including the fence that encircles the cemetery today– and rename it Minneapolis Pioneers and Soldiers Memorial Cemetery to commemorate the city’s first settlers and war veterans.

Today the cemetery is maintained by the City of Minneapolis, the Park Board and a creative Friends of the Cemetery group that is working to preserve this site and make it more accessible to the surrounding community.

Map is from the Minneapolis City Archives at City Hall. Material for this post was taken from the Layman’s Cemetery collection at the Hennepin History Museum and the Friends of the Cemetery website.