A cancer at the heart of the city

It’s map Monday. This week we’re going to return to the Gateway District, the heart of the historic city. Questions about its fate–formulated in conversation with collaborator James Eli Shiffer –were responsible for launching the Historyapolis Project three years ago.

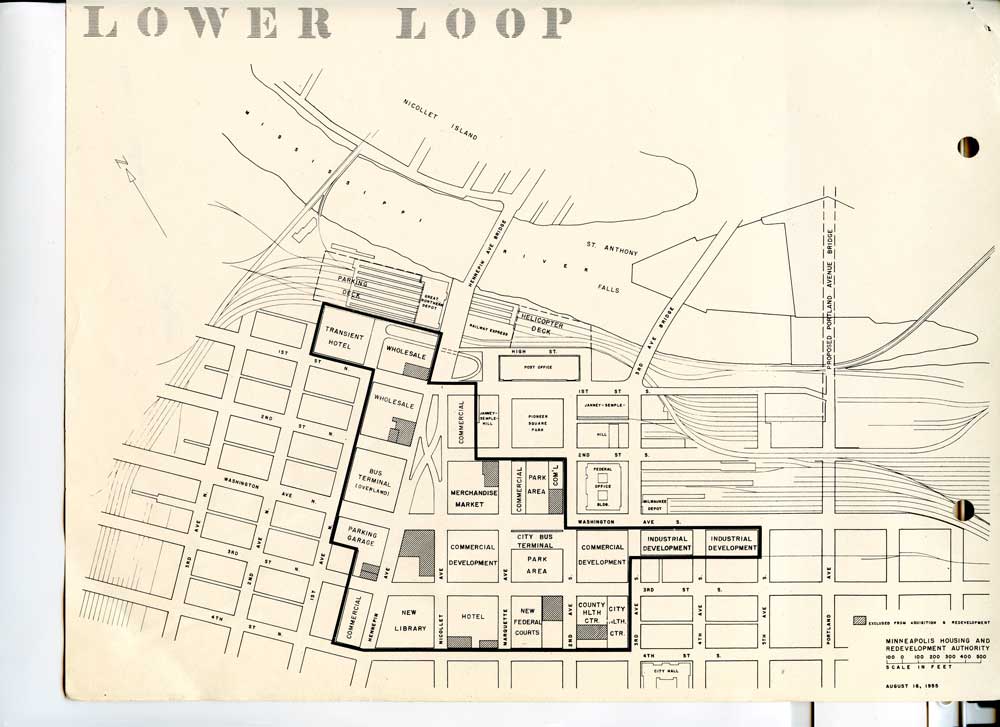

This map delineates the 25 block section of the city that city planners decided to demolish in the 1950s. With the financial backing of the federal government, they launched the Gateway Center redevelopment project–the largest urban renewal project ever undertaken in the United States up until that point–and flattened the center of the city between 1958 and 1963. This is only one of dozens of maps created by city planners that Historyapolis researchers have found in the tower archives at City Hall and the collections of the Community Planning and Economic Development department at the city of Minneapolis.

By the early twentieth century, the Gateway had become a source of tremendous frustration for city leaders. Minneapolis had solidified its national and international reputation as the “Gateway to the Northwest”; the Mill City had just beat out St. Paul in a “census war” that established it as the largest city in the region. New residents were flooding the city, which seemed unrivaled as the region’s financial and industrial capital.

But all of this growth and prosperity had a darker side, which city boosters loved to ignore. “The Shame of Minneapolis”–published in 1903 by Lincoln Steffens in McClure’s Magazine–highlighted the shocking level of municipal corruption in the Mill City. Visitors to downtown were also confronted by conditions in the Gateway, which had become the region’s largest skid row.

The Gateway provided homes and services to the thousands of workers demanded by Minneapolis mills and factories. With wages insufficient to fund the kind of domestic life admired by middle-class Minneapolitans, these workers found in the Gateway cheap housing and information about the day labor jobs that allowed them to eke out an existence. The city charter concentrated the liquor business in the district. And through a structure of fines and regulation, the city had forced the commercial sex trade to focus here as well.

By the beginning of the twentieth century, the die was cast for the Gateway. Its streetscape was dominated by flophouses, bars, liquor stores, missions and secondhand clothing stores. The district became a magnet for anyone in the region looking for illicit sex, the camaraderie of an all-male environment, a place you could drink undisturbed and find inexpensive comfort food.

The city made several attempts to rehabilitate the district, developing Gateway Park in 1915 with its wonderful Beaux-Arts pavilion and the new central post office in the 1930s. But the neighborhood continued its downward spiral.

By the 1940s, the Gateway was home to approximately 4,000 older men who had spent the first decades of the twentieth century harvesting crops, building railroads and felling timber. One-time lumberjacks, gandy dancers and farm hands, their perambulations had been circumscribed by changing economics and advancing age. They established what was for many a comfortable routine, subsisting on pensions and fixed incomes, circulating within a tight circle of bars, liquor stores, flop houses and missions.

These men exasperated city leaders, who viewed them as “homeless” despite their fixed residence in the neighborhood’s cage hotels. City boosters viewed the Gateway as a cancer that threatened the health and vitality of the entire community. Radical surgery was the only solution. This conviction prompted them to demolish 40 percent of the city’s downtown.

This scorched earth redevelopment project left a sterile landscape in this part of town. Until the building frenzy of the last several years it has been dominated by surface parking lots. This latest round of development begs the question–is the long winter of the Gateway Center development finally over in Minneapolis?