“It would hardly be an open shelf book”

Today’s guest blogger is JaneAnne Murray, a solo criminal defense lawyer based in Minneapolis and also Practitioner in Residence at the University of Minnesota Law School, where she teaches classes in criminal law and procedure. Tonight, she is presenting a Bloomsday Celebration in New York City for the Irish American Bar Association of New York, the centerpiece of which is the Quinn Memorial Address, to be delivered by the Hon. Gerard E. Lynch, Second Circuit Judge.

Happy Bloomsday! This is the day, 110 years ago, that was memorialized in James Joyce’s masterwork Ulysses – a brilliant, scatological, and lyrical journey through the streets of Dublin and the deep recesses of the mind of the book’s protagonist, Leopold Bloom.

The publication of the book in this country was an odyssey too, beginning in 1917, when two feisty mid-western women living in Greenwich Village, Margaret Anderson and Jane Heap, decided, with alacrity, to serialize the book in their literary publication, The Little Review. The magazine’s motto was “Making No Compromise with the Public Taste,” and did it not! The serialization didn’t manage to get to the end – Bloom’s masturbation on the beach while oogling the sexy Gerty MacDowell was simply too much for the secretary of the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice, who complained to the Manhattan District Attorney. In 1921, Anderson and Heap were prosecuted for distributing obscene material, and were defended pro bono – and some say half-heartedly –by Irish-American lawyer John Quinn, who famously described his clients as “idiots” and “damned fools” for trying to publish Ulysses in this “puritan-ridden country.”

Their conviction at trial could be viewed as a devastating blow for the First Amendment, or a public relations coup. In the ensuing decade, during which no American publisher was willing to risk a prosecution or, at least, afford the financial calculus of publishing the book, Ulysses took on the mystique of the forbidden fruit – smuggled past U.S. customs officials, hidden in waistbands and luggage, and sold by bootleggers for hundreds of dollars. In 1932, however, social mores had relaxed, and Random House – eyeing both a sales and political coup – decided to seize the moment. It orchestrated one of the most sophisticated litigations of its time, selecting a brilliant advocate, an enlightened venue, and a sympathetic judge to challenge the U.S. ban on Ulysses in U.S.A. v. One Book Called Ulysses. The seizure of the book was a carefully planned affair – indeed the specific book to be seized was filled with all sorts of clippings, including literary reviews, so that these too would automatically be placed in evidence. Unfortunately, the plan almost went awry. The customs agent, when he saw the familiar blue cover, was about to waive the item through, and the Random House representative had to beg him to seize it!

And thus began the famous case. As part of its defense strategy, Random House solicited the views of librarians and booksellers across the country on their interest in purchasing a reasonably-priced copy of the book. The solicitation was hardly disinterested. It noted that Ulysses critics deemed it “the most significant prose work of the twentieth century,” Random House thought the ban on the book “unconscionable and vicious from the point of view of letters,” and its survey was aimed at rallying “intelligent and qualified public opinion” in defense of the book. It then proceeded to ask the recipient for their “frank” opinion . . .

324 responses were returned, offering us a fascinating window into the literary and social tastes of the day. They include such nuggets as “I’m inclined to doubt its value as literature, for I have never been convinced Mr. Joyce knows how to write English;” “Never will it have any readers to amount to anything;” “It is literary jazz, intriguing for sophisticated half morons;” “I read it and found it insufferably dull – not good enough to be worthwhile and not bad enough to be interesting;” and this from a librarian in Los Angeles: “It is read here entirely by those wanting salacious literature. Our copy is practically untouched, except for the last 100 pages, which proves my point, I believe.”

Three of the questionnaires came from Minneapolis, and the views expressed were cautious but respectful. All three acknowledged that the work likely had literary merit, but none believed the book should be freely available. Florence Mettler said she would buy a copy of the book for the North Branch of the Minneapolis Public Library, but added “it would hardly be an open-shelf book.” Lou Gordon, chief of the order department at the Minneapolis Public Library, said they already had a copy, though “[i]t would not be and could not be a book for general circulation in a public library.” He added that he thought the book’s psychological importance was “much exaggerated.” Finally, famed Chief Librarian Gratia Countryman (who would be elected president of the American Library Association in 1934 and was considered one of the most influential librarians in the country) acknowledged that she had not read it, but agreed it had “perhaps [.] influenced the stream of consciousness style.” From critical reviews, however, she felt “sure that it would belong on restricted shelves.” Her library “probably would not buy [it].”

Oral argument was heard on the case in 1933 before Southern District of New York Judge John Woolsey. In his presentation, Ulysses defense lawyer, Morris Ernst, highlighted some of the more favorable comments from the questionnaires – prosecutor Samuel Coleman would have had a field-day with the negative ones. But in the end – perhaps a foregone conclusion – Judge Woolsey issued his milestone legal decision on obscenity, holding that Ulysses, while tending towards the “emetic,” was not “aphrodisiac.” Deciding to admit Ulysses into the United States, the judge was unfazed by “the recurrent emergence of the theme of sex in the minds in [Joyce’s] characters.” After all, “it must always be remembered that his locale was Celtic, and his season spring.”

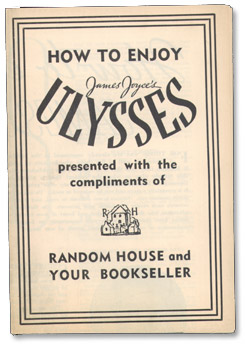

Random House immediately ordered a printing of 100 copies. It included Judge Woolsey’s decision at the front of the book, to ensure that if news of the overturning of the ban did not filter down to the beat cop, a reader facing confiscation could open the book and spread the word.

The questionnaires quoted here are from the Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas. “How to Enjoy Ulysses” is from the James Joyce collection at the University of Buffalo in New York. Thanks to both of these institutions for sharing their materials with Historyapolis.