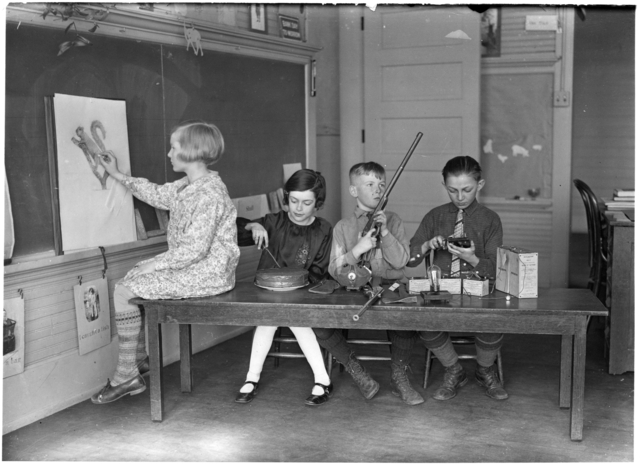

Back in the day, you could bring your guns to school

Students return to school in the Minneapolis Public Schools today. These two photos celebrate the start of a new academic year.

At the top we have a 1925 scene from a “hobby fair” at Burroughs Elementary School, which was an opportunity for the children to share their hobbies with classmates. This image shows one girl painting while another decorates a cake. On the other end of the table, a boy was operating something electronic, perhaps a radio set? The jawdropper in this photo is the middle boy, who seems to be showing off his firearm collection. He appears to be demonstrating the operation of his rifle (which might be a toy, like the Red Rider BB gun in A Christmas Story). In any case, it shows that times (and policies) have changed in schools across the United States.

For those of you curious about the history of schools in Minneapolis, follow this link to learn about the origins of school names. Compiled in 1923 (when 70,000 kids were enrolled in the MPS–more than double the current enrollment), it’s a wee bit incomplete. But it’s still informative. Did you know, for instance, that Pratt School was named for the first Minneapolis soldier to die in the Philippines?

The second photo shows children in a singing class at Whittier Elementary school, also in the 1920s. This adorable image is notable because it shows a classroom with both white and African American children. Then as now, the Whittier neighborhood was one of the most racially diverse in the city. The school reflected its environs, bringing an economically and racially mixed group of children together.

The 1920s marked a turning point for race relations in Minneapolis. Immigration from Europe was declining dramatically. At the same time, thousands of new African Americans were arriving in the city from the South. In the decades that followed, the Minneapolis Public Schools would become increasingly racially segregated. Children attended the schools closest to their homes. And restrictive real estate covenants and discriminatory rental practices kept non-white residents concentrated in a few parts of town. Schools reflected these housing patterns, which were enforced by custom, intimidation and sometimes violence.

City leaders began to see school segregation as a problem to be addressed in 1967, when John Davis became superintendent in Minneapolis. Davis pushed integration at all levels, hiring African Americans as teachers and administrators and support staff across the district. And he began to work on creative ways to bring children from different backgrounds together in classrooms. Out of this desire came the plan to “pair” all-white Hale School with the all-African American Field School. The idea was to put the younger children from both schools at Hale and the older kids from both kids at Field.

First day of busing in Minneapolis, 1971. Monica Lash (left) and Molly Johnson (right) were two of the hundreds of children who were bused as part of the Hale-Field school pairing experiment.

The reaction to this plan–at least in some quarters–was less than positive. After the plan was announced in 1970, school board member Harry Davis remembered that he needed a police escort to get home and round-the-clock police protection while he slept. Mayor Charlie Stenvig–who had been elected in 1969 after tapping fears of racial violence in the city after unrest on the North Side–helped to rally opponents of busing, who jammed community meetings.

Despite this opposition, the city had little choice but to proceed with a sweeping integration plan in 1972, after federal judge Earl Larson decreed that Minneapolis had “intentionally and deliberately” kept students segregated.

Forty-five years later, Minneapolis schools continue to be segregated. And the district continues to struggle with how best to create diverse learning environments that meet the needs of all students.

Today, if we need to find inspiration to meet this challenge, we need to look at the sweet faces in the ninety year old photo from Whittier School.

Information for this post comes in part from Harry Davis’ autobiography, Overcoming. Images are from the collection of the Minnesota Historical Society.