“It was our university”: Sumner Library and the old Sixth Avenue North

Sumner Library is celebrating its centennial this Saturday.

You may shrug. But this really is a cause for jubilation. And a moment to contemplate the diverse history of one of Minnesota’s most interesting neighborhoods.

This lovely little library on the city’s north side–built with funds provided by Andrew Carnegie in 1915–has served as a critical institution in one of the state’s most diverse neighborhoods for 100 years. “It was our university,” one patron remembered at the 50th anniversary of the library. It was here that generations of new arrivals “learned to be American,” declared Harrison Salisbury, Pulitzer prize winning journalist who grew up in a dilapidated Victorian mansion nearby in the early twentieth century.

A native son of the near north side, Salisbury was an anomaly. The grandson of a prominent Minneapolis physician, he was one of the only children in his neighborhood whose families had been in the city for any length of time.

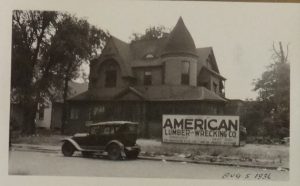

A home in the Oak Lake Addition in 1936, right before the area was demolished for the construction of the farmer’s market. Photo is from the Minneapolis city archives, Minneapolis City Hall.

Salisbury grew up in the Oak Lake Addition, which had been originally conceived as an “exclusive district” in 1880. Yet by the time that Salisbury was a child, the district had lost many of its most prominent families and his neighbors were largely newly arrived Russian Jews. “There was bitter opposition to the Jewish invasion,” according to sociologist Calvin Schmid, who later described how the neighborhood became dominated by Jews and then African Americans. But Salisbury remembers this shift as a gift. He was thankful for the opportunity to grow up in “the most alien corner of that most Middle Western city of Minneapolis.”

Bronchin’s delicatessan, c. 1914. Sixth Avenue North in Minneapolis. Image from the Minnesota Historical Society.

The commercial spine of Salisbury’s neighborhood was Sixth Avenue North, which was lined with immigrant businesses that sold basic provisions like bread, eggs, potatoes and crackers as well as matzohs, prayer shawls, mezuzahs and kosher meat necessary for observant Jews. On the same stretch, residents could get their shoes repaired or their clothes laundered in a Chinese laundry. While they were waiting for their garments they could enjoy a Turkish bath (a necessity in a quarter where many dwellings did not have indoor plumbing).

Members of the Workman’s Circle at the Labor Lyceum. Photo from the University of Minnesota Libraries, Nathan and Theresa Berman Upper Midwest Jewish Archive.

Up the street was the Labor Lyceum, which hosted debates on socialism and served as a cultural hub for radical Jews. Those less politically inclined could pay a nickel at the Liberty Theater and lose themselves in the Perils of Pauline. After the film they could stop two doors down for an audience with notorious gangster Kid Cann, who kept a headquarters next to one of the many pool halls on Sixth Avenue North.

The street offered round-the-clock entertainment with its constant flow of peddlers and delivery people. Children scavenged in the wake of the ice wagon and the coal wagon; they followed the popcorn man and the waffle man on their rounds. In the summer, those without the fifteen cents for one of these sugar-drenched confections tried to satisfied their hunger with “soft tar from the pavement in the hot sun,” according to Salisbury, which they chewed “in place of Spearmint.”

The library became part of this lively streetscape in 1912, when it opened in a storefront. Three years later it moved into its permanent home, which was constructed with $25,000 from the Carnegie Foundation. Librarians welcomed children, taught them to read and sent them home with armloads of books. The building’s gothic reading rooms became a favorite gathering place for children, who went there to be cool in the summer and warm in the winter.

Twenty-three years after its construction the building was moved 100 feet to the north, to make way for the new Olson Memorial Highway. A crew of six men used a large jack to shift the building one -eighth of an inch at a time. “It was,” according to Sumner Branch Librarian Adelaide Rood, “a major feat of delicate engineering.”

Sumner Library was the only building considered worth saving when the new thruway was constructed. Many residents had none of Salisbury’s nostalgia when they remembered the “speakeasies, tippling houses, gambling joints and brothels” of the intersection they called “the Hellhole.” They cheered when this notorious commercial district fell under the bulldozer, as the city kicked off what would become a fifty year campaign to eliminate urban blight. Cars replaced walkers, gutting the heart of this immigrant quarter.

Through all these changes, Sumner Library endured, opening its doors and the world to generation after generation of new arrivals to Minneapolis. Daniel Bergin interviewed many of these patrons for Cornerstones, his 2011 documentary, which narrates the history of north Minneapolis through the stories of its critical institutions.

This Saturday, take the opportunity to visit this Minneapolis landmark. Visit Sumner library from 12-4 pm and join in this celebration of its storied history.