“The last outpost of urban paradise”

The nation was grappling with twin threats in June 1973, when a photographer named Donald Emmerich visited Minneapolis. The “urban crisis” had dovetailed with anxieties about the environment to make many Americans question the viability of city living. The newly created Environmental Protection Agency had hired a team of photographers–which included Emmerich–to document how ordinary people were confronting this challenge.

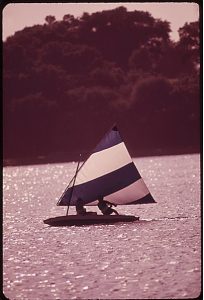

Yet when Emmerich came to Minneapolis, he saw little that could be called blight or despoilation, though he did record some shots of sewage pipes and junkyards on the Mississippi River. He found an urban environment where the denizens seemed to be in harmony with one another and their natural surroundings. He saw Minneapolitans strolling, lounging and riding their bikes on a newly created downtown shopping street, Nicollet Mall. And he observed how residents enjoyed their city lakes. The photographer spent a long summer evening watching sailboats on Lake Calhoun, creating a series of images that could have been made into postcards for the Chamber of Commerce.

Emmerich was employed by DOCUMERICA, which took inspiration from the federal documentary projects of the 1930s. DOCUMERICA sought to show the relationship between American people and their environment, creating 15,000 snaphshots of everyday life in 1970s America. The images of Minneapolis stand out in this unique collection, which is now housed at the National Archives. The city provides a happy contrast to views of belching factories, deteriorating buildings and burning rivers. With its bikes and lakes and leafy streets, Minneapolis emerges as a model metropolis, a bright spot of hope in the nation’s “urban crisis.”

Emmerich’s work reflects popular perceptions of the city in these years. His images of Lake Calhoun and Nicollet Mall give visual proof to the boasts of city leaders, who asserted that Minneapolis was an urban center without urban ills. This vision of the city provided the backdrop for the Mary Tyler Moore show, which aired between 1970 and 1977. Its iconic opening trailer–which featured the show’s star tossing her tam in the air on Nicollet Mall each week–helped to fix Minneapolis in the national cultural imagination as a city unburdened by urban blight. Minneapolis was “the last outpost of urban paradise,” one Dayton Hudson executive told Fortune in 1976. “This was a city,” The New York Times later observed “that seemed to have all of the answers.”

This hyperbole hid some uncomfortable realities. New surface parking lots covered much of downtown after the bulldozing of the historic Gateway District in the early 1960s; police brutality had helped to launch the American Indian Movement in 1968; growing racial disparities had fueled unrest and violence on Plymouth Avenue in 1966 and 1967. Yet by the 1970s these struggles had all been obscured by idyllic images like Emmerich’s photograph of Nicollet Mall. The myth of the model metropolis buried the city’s history of conflict. And our civic identity has remained fixed, in many ways, in these images of the 1970s. This has made it difficult for us to grapple collectively with the legacies of some of our difficult episodes in the city’s history.

This golden age for Minneapolis inspires intense nostalgia today. And there is no better way to indulge these yearnings than to visit the Mill City Museum, which has just opened a new exhibit of downtown street photography from this period. From 1972 to 1974, when he was a suburban teenager, Mike Evangelist took hundreds of photographs of downtown Minneapolis. Each afternoon he wandered downtown before reporting for his shift at the downtown post office. These explorations introduced him to a slightly grittier side of the city than the one discovered by Emmerich. He was fascinated by quirky street characters and scruffy streetscape; the resulting images will tantalize anyone who has ever spent any time in downtown Minneapolis.

Evangelist’s images show a place that is both alien and familiar, according to Andy Sturdevant, who wrote the text that accompanies the images in the exhibit and companion book published by the Minnesota Historical Society Press. They portray a city that defies stereotypes of this decade; it is neither model metropolis nor showcase for urban blight. These photographs do no more than Emmerich’s to reveal the hidden history of Minneapolis. But they will delight urbanophiles, reminding us of the joy and surprise and intrigue of our earliest encounters with cities.

Image credit: Documerica Collection, National Archives and Records Administration.