Map Monday: Seven Corners in 1915

It’s Map Monday.

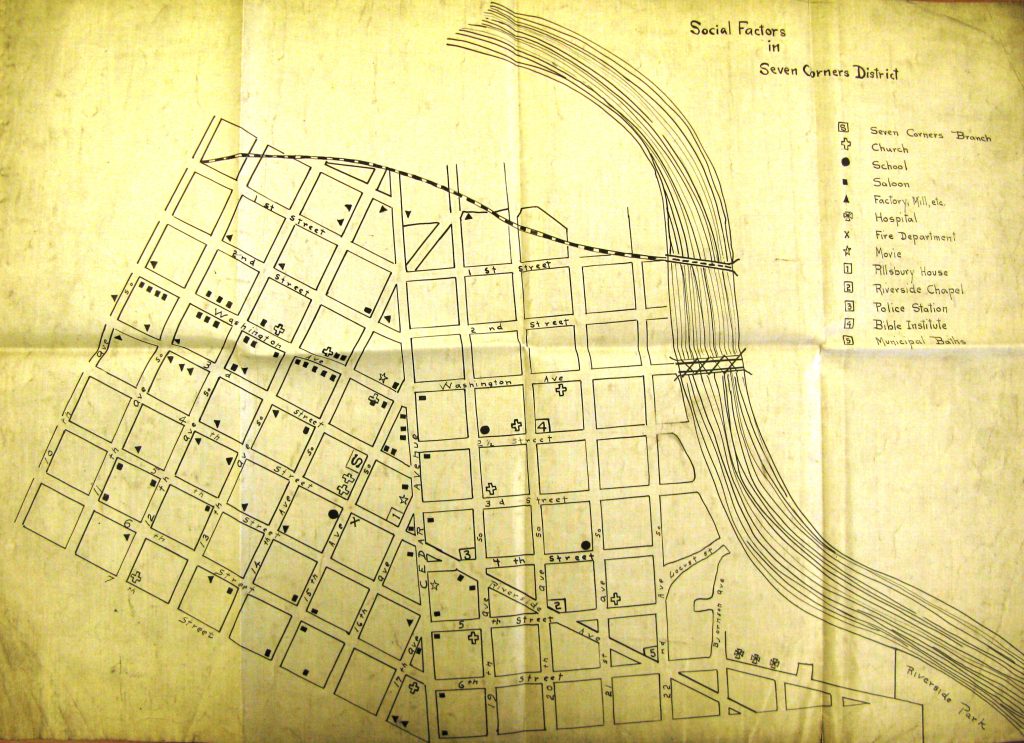

Seven Corners librarian Grace Stevens drew this map to accompany her 1915 “Community Report,” a description of the Sixth Ward that surrounded her library building on Fifteenth Avenue South and Third Street. This small branch library had started as an experiment in 1906, the joint effort of the Minneapolis Parks Board, Riverside Chapel and the library board. It was so heavily used that the library constructed a building in 1912; from all reports it immediately became a community center in a part of the city where social needs were enormous.

Stevens summoned a range of sociological data to paint a portrait of life in the Sixth Ward. Ninety percent of the residents in this district had been born outside of the United States. These newcomers found shelter in one of the most congested parts of the city, where “four or five families sometimes” lived ” in one dwelling,” Stevens explained. “Some low, dark buildings contained, besides several families, rooms for lodgers,” she wrote. In these rooming houses, single men were packed so tightly they sometimes shared their beds with total strangers. Residents sought to escape these cramped living quarters whenever possible.

Saloons were the biggest draw in the neighborhood, “there being sixty-four in the ward,” Stevens enumerated. Her map indicated their locations with black squares. But residents were also drawn to movie theaters and dance halls, which Stevens perceived as equally dangerous sources of corruption. Children had few desirable destinations. Since there was no accessible playground, they “have only the street in which to play.” And the neighborhoods avenues were not even attractive, since “unsightly scrap iron heaps and bill-boards add to the general ugliness.”

A significant asset was the Municipal Bath House, which was located on Riverside and 22nd Avenues. She reported that more men than women used the facility, which was “equipped with showers, bath tubs and swimming pool.” Showers cost two cents, with an additional two cents charged for soap and towel. These baths were essential for community health since most of the homes in the Sixth Ward “have none of these conveniences necessary in the rearing of healthy children.”

Stevens sought to make the reading room of the Seven Corners library into a cozy enclave in what she perceived to be a bleak urban landscape. She saw her library as a community “parlor,” where children could spend the hours they were not in school and seasonal laborers could read by the fire in their months of leisure. She tried to acquire books in Swedish, Russian, Bohemian, Finnish, German, Hebrew, Hungarian, Lettish, Polish, Roumanian, Yiddish, and Norwegian. She bought checkers sets. She cultivated a flower garden next to the sidewalk. She organized weekly concerts. She started clubs for children. She worked–whenever possible–with the Pillsbury House, which provided child care and classes for children and families.

The librarian despaired over the allure of radical politics for many of her patrons, who were loyal to the Socialist Party. The Socialists controlled voting in the ward, which also had a large contingent of residents drawn to the radical IWW, which she jokingly claimed was shorthand for “I Won’t Work.” It was her desire that the library “will help to convince them of their equal chance with their more fortunate brothers.”

Stevens’ map is part of the Seven Corners’ branch library collection at the Minneapolis Collection at the Hennepin County Central Library. My thanks to historian Andy Wilhide, who first showed me this map and this collection.