Minneapolis in 1948: ”Where in the heck do black people live around here?”

Matthew Little, civil rights leader, died this past Sunday at the age of 92. A leader of the Minnesota delegation of the 1963 March on Washington, Little was the long-time president of the Minnesota NAACP. He fought to open up hiring practices. He battled segregation in the state’s public schools, filing lawsuits that brought seismic changes to education in Minneapolis. He was a huge force for justice in Minnesota.

A native of Washington, North Carolina, Little had left the South after being denied admission to medical school. In 1948, a flip of a coin sent him to Minneapolis, where he had neither friends nor family.

Little later recounted his earliest days in the city, which was earning a national reputation for racial liberalism thanks to mayor Hubert Humphrey and his municipal Fair Employment Practices Commission. That summer at the Democratic National Convention, Humphrey would put the city on the map when he demanded that the Democratic Party “get out of the shadow of states’ rights and to walk forthrightly into the bright sunshine of human rights.” But when Little actually arrived in Humphrey’s city, its cold streets were less-than-welcoming to a young black newcomer from the South.

Little “stayed at the YMCA downtown for four days. I walked around the downtown area. I felt so out of place because I didn’t see another black person those whole four days. The other thing was I didn’t realize it was going to be so cold, either.”

Little wandered until he found a police officer and said “”Where in the heck do black people live around here?'” The cop replied: ” ‘Well, I’ll tell you; if you go down between Third and Fourth Avenue, there is a bar that’s owned by a colored person. I’m sure if you go in there you would find some coloreds.’ So I followed his directions and I went there and sure enough it was full of black people. They really looked good. I hadn’t seen any for a while. I sat there at the bar and struck up a conversation.”

Little had found the city’s south side African American community, a small group of businesses and homes clustered along 4th Avenue, south of Lake Street. His first stop was probably the Dreamland Cafe, which was owned by Anthony B. Cassius, a labor activist and “race man.” In the bar, Little remembers that “the first thing I asked was where could a person find someplace to stay. They told me to take that streetcar on Fourth Avenue and get off at 38th Street. There was a barbershop there. Ask somebody in that barbershop and they will tell you where you can find someplace to live. So I did and they told me that up on 41st and Fourth Avenue, the second house from the corner, there was a lady by the name of Mrs. Smith that was taking in renters. That I did. That’s how I got in contact with Minneapolis, Minnesota.”

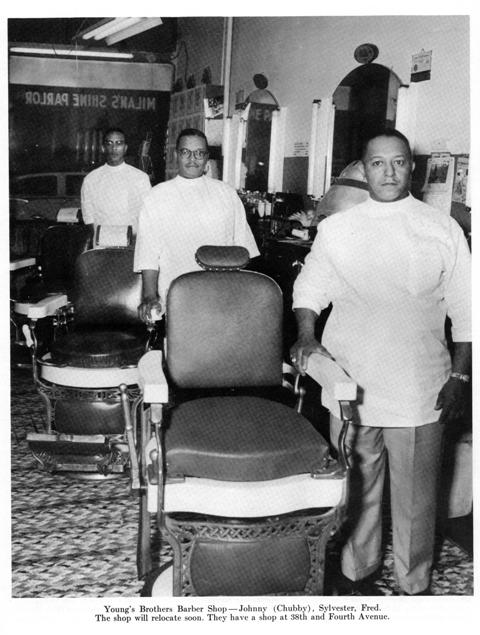

Little “got in contact with Minneapolis” through the Young Brothers’ barbershop, shown here in a 1954 photo from the Minneapolis Beacon. Barbershops like this one served as conduits for information and activism in African-American communities across the country.

Despite Humphrey’s efforts, Little found it almost impossible to get a job. “Well everyplace that somebody that would tell me, I put in a resume. They would smile and say, “OK, we’ll give you a call.” But nothing happened,” he remembers. At the Minneapolis Fire Department, Little aced the physical and written exams but “failed” the interview. This experience with discrimination would launch his career as an activist. As part of this fight, he would later join a federal lawsuit aimed at opening up hiring practices.

After a stint as a waiter at the Curtis Hotel, Little decided to go into business for himself. He did landscaping, combining this work with civil rights activism for many decades.

Matthew Little’s interview is excerpted from Jerry Abraham Voices from Minnesota: Short Biographies from Thirty-two Senior Citizens (DeForest Press, 2004).

The photo of the Young Brothers Barber shop is from the Centennial Edition of the Minneapolis Beacon: Featuring the Negroes in Minneapolis (A Scott Publication, 1956). It can be found in the Minneapolis Collection at the Hennepin County Central Library.