Crime and Technology

The police in Gilded Age Minneapolis were overwhelmed. In the last quarter of the nineteenth century, the population of the infant city exploded from 13,000 to 200,000. Newcomers landed in the city every day, traveling from all corners of the globe in search of new opportunities.

Honest strivers made up the vast majority of this influx. But the world’s criminal element also was attracted to the booming polyglot city. The question for police was how to distinguish the one from the other. Like colleagues all over the world who were seeking to systematize and professionalize law enforcement, the Minneapolis police decided to invest in technology.

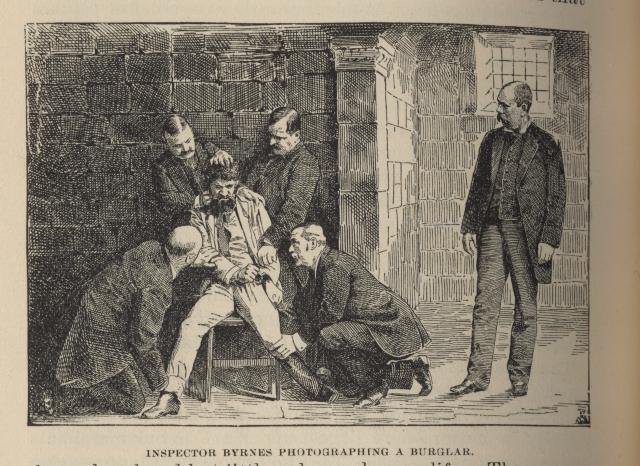

In 1877, the police asked the city council to appropriate $25 annually to fund a modest experiment with the new technology of photography. The department sought “occasionally have the photographs of noted criminals and desperadoes taken.” Photography was known, according to contemporary writer Augustine Costello, to deter crime since “when such parties knew the police had their photographs they were more apt to keep clear.”

This faith in the power of the image sounds somewhat naive to modern readers, who understand how photography is a narrative tool that can be manipulated to tell different stories. For inhabitants of the late nineteenth century, however, photography promised immutable and scientific images. It suggested that identities could be fixed, allowing police to track down the shysters, swindlers and common criminals who sought to elude capture by moving across municipal, state and even national borders. It pierced the anonymity afforded by unprecedented urbanization and massive global migration, allowing law enforcement to tighten the noose on habitual offenders.

The 1877 appropriation reflected the ambitions of city leaders, who imagined their village on the river growing into a great global metropolis. They wanted a police force that was as modern and efficient as the city’s industry and recognized that information was as valuable to law enforcement officials as to grain traders and lumber barons.

Minneapolis became a global economic player. But it was never on the cutting edge of law enforcement. Over time, the police department amassed a rogue’s gallery of suspects and convicts. But after photography, the police were reluctant to embrace new developments in criminal science. Until the middle of the twentieth century, the department remained mired in a series of municipal corruption scandals. The police in Minneapolis were known less for their crime fighting and more for their cooperation with local n’er do wells.

Thirty years after the Minneapolis police began using photographs, the force adopted the Bertillon System, which was named for its creator Alphonse Bertillon, a Paris police clerk. This system for tracking and classifying criminal behavior came to Minneapolis in 1907, just as many cities around the world were abandoning it. More on that in later posts.

This image is taken from Augustine Costello, History of the fire and police departments of Minneapolis, published in 1890. It shows a Minneapolis detective as he struggles to photograph a burglar.