The Bertillon System: Science and Crime in the Global Information Age

Today’s blogger is Stewart Van Cleve, a graduate student in the program for Library and Information Science at St. Catherine University. The author of Land of 10,000 Loves: A History of Queer Minnesota, Stewart discovered the tower archives at Minneapolis City Hall when he was researching the history of gay sexuality in the city. He has joined forces with Historyapolis this month to illuminate the holdings of this forgotten cultural repository.

On a dusty shelf in the tower archives at Minneapolis City Hall sits a line of oversized leather volumes. These are the remnants of the city’s Bertillon ledgers, which served as the intake logs for the Minneapolis Department between 1907 to 1921.

Bertillon records, Minneapolis City Archives, April, 2014. Photo by Historyapolis volunteer Lisa Lynch.

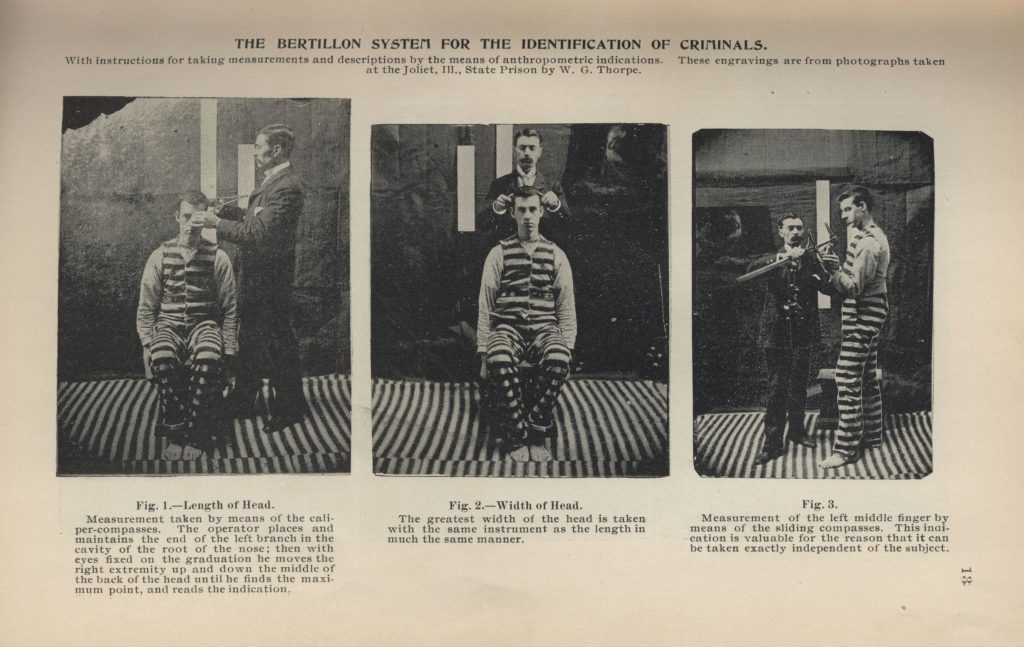

Paris police clerk Alphonse Bertillon developed this system for identifying criminals in 1883. These photographs illustrate how the system was supposed to work. Officers were instructed to make an elaborate set of anthropomorphic measures of each suspect. The length and width of the head, the length of the right ear, the size of the feet and the length of the left, middle and little fingers were all recorded. Taken together, these measurements created an unique set of statistics. Each person on the planet–according to Bertillon–could be reduced to a set of body measurements which they shared with no one else.

The Bertillon system imposed an order to criminal classification and allowed police to discover the “real” identities of the people in their custody. It created a common language for police all over the world. The number sets could be shared–via telegraph–with other law enforcement officers. This global network was intended to prevent habitual criminals from slipping from one police jurisdiction to another without detection.

The Bertillon system was introduced in the United States in 1887 and immediately “became the distinguishing mark of the modern police organization,” criminologist Raymond Fosdick explained in 1915. It came to Minneapolis twenty years later. Until this time, the police had relied entirely on their “rogue’s gallery” of photographs to track suspects.

Once they adopted the Bertillon system, the Minneapolis police recorded body statistics as part of their intake procedure. In addition, they also wrote short details about their suspects—their race; their ethnicity; their age; their address; their behavior—and the crime: its location, its details, and sometimes its body count. The notes are possibly the most interesting and unique feature of the ledgers: intended as internal communication among officers, they offer insight into how the police saw the people they captured. Occasionally, officers even used the ledgers as scrapbooks; they pasted newspaper clippings about the crime on the back of the record.

In most cities, the Bertillon cabinet included photographs that may still reside somewhere in the city. Even without the accompanying photos, the Tower Archives’ Bertillon Collection is possibly one of the last of its kind.

The system never functioned in the way that Alphonse Bertillon envisioned. As the photographs here might suggest, the measurements were difficult to record with precision. In Figure 4, “operators” are instructed to “have the subject take the position indicated by the engraving on a firm solid bench. This position will force the most stupid or wiley person to place himself in a proper position so the measurement will be accurate.”

By the time of Bertillon’s death in 1914, most criminologists considered his system obsolete. “Its fundamental inferiority to the simpler, surer system of dactylosopy,” or fingerprinting, criminologist Fosdick declared, “makes inevitable its final downfall.” But the city maintained the ledgers until 1921.

A century after their creation, the Bertillon ledgers offer no scientific overview of crime in Minneapolis. But they do provide fascinating reading. Each entry is a tantalizing glimpse into the underworld of early twentieth century Minneapolis. In the days to come, we’ll share a selection of these entries with you.

Images are from Alix Muller and Frank Mead, History of the police and fire departments of the Twin Cities: their origin in early village days and progress to 1900 (Minneapolis: American Land & Title Register Association, 1899). This book is from the Minneapolis history collection at Hennepin County Library Special Collections.